Article written by me for The Japan Times

On June 25, 1863, a Royal Navy team drawn from officers on ships sent to protect British expats in Japan had plenty to worry about as the lanky James Campbell Fraser strode out to bat against them on an apology for a cricket pitch in Yokohama.

A swashbuckling Scot, Fraser had played cricket while at Harrow, a fee-paying school well known, along with Eton, for educating the country’s ruling elite. Though he didn’t make its first team, both there and later while working in Liverpool — where he played in a game against an All-England XI — he had encountered some fine players before arriving in Japan in 1862. So the following year, on that grassless patch of reclaimed land by the Foreign Settlement, his cricketing pedigree was a toffee-nosed head and shoulders above the rest.

As the fielding Royal Navy players retreated just a little in anticipation of Fraser’s fabled big-hitting, the batsman for the Shore side can hardly have failed to notice the pistol set down behind the stumps.

“It was a most novel sensation for the wicket-keeper, as he carried his revolver backwards and forwards from wicket to wicket and placed it behind the stumps,” Fraser wrote in the April 16, 1908, issue of London-based Cricket magazine. He explained that the teams “played with their revolvers on, ready for any emergency,” and that the ground was guarded after “a small force armed with rifles was landed from the men-o’-war for protection.”

Similarly, the future polar explorer Admiral Sir Albert Hastings Markham, who played in the match as a young lieutenant, noted, “It is, I suppose, the only match on record in which the players had to be armed.”

Welcome to the remarkable events of what Fraser only refers to as a “certain day” — though it was one that actually saw the first-ever game of cricket in Japan.

Notwithstanding his prowess with the bat, both teams’ players were armed and edgy because June 25, 1863, had been declared — in the name of Shogun Tokugawa Iemochi — as the day to start killing foreigners who ignored his order to leave.

In those days, a decade after U.S. Navy Cmdre. Matthew Perry’s so-called Black Ships appeared off Edo (present-day Tokyo) to begin prising Japan open after more than two centuries of self-imposed international isolation, foreign residents were still shaken by the murder in Namamugi, outside Yokohama, of an English merchant named Charles Richardson in the previous September.

Out riding with friends, the 28-year-old — who was stopping over en route home from Shanghai — was killed by bodyguards of a Satsuma noble whose retinue he disrespectfully approached too closely.

With Britain and Japan at loggerheads over the resulting compensation demands, Yokohama was no place for the fainthearted foreigner as spring turned to summer in 1863.

According to Fraser, “The European residents, who were few in number at that time, had been frequently warned from Japanese sources that they were going to be assassinated by a band of disaffected samurai, but they had been warned so often, without anything happening, that they had come to look upon the whole thing as a joke.”

That June, however, the situation took a sudden turn for the worse, even though extra Royal Navy warships had recently arrived, ready to use force to back up Britain’s huge reparation demands for the killing.

“A warning came from the Charge d’Affairs, Col. St. John Neale, who at that time resided in the British Legation in Yokohama, that they were going to be attacked on a certain day,” wrote Fraser, citing June 25 as the day in question.

“He advised Englishmen to leave Japan and proceed to China as he doubted his ability to protect them. This they were willing to do if he, on behalf of the British government, would guarantee to compensate them for the loss they would sustain through leaving the country,” wrote Fraser.

As Neale was unable to do that, they resolved to stay and defend themselves, if attacked, relying heavily on the Royal Navy presence in the harbor.

“As the day approached on which Col. Neale had said the attack was to be made,” wrote Fraser, “the native population of Yokohama, including the servants, cleared out bag and baggage. This meant no business was to be done, and the Englishmen naturally wondered how they should pass the time, for they dare not leave the settlement and go into the country. A cricket match was suggested and a challenge sent to the Fleet.”

However, the real motive for scheduling the match on June 25 was surely not just a spirit of sporting friendship but the isolated residents’ fear of attack and their desire to have armed guards close by rather than on ships in the port.

And so we return to 23-year-old Fraser, the Shore team’s best batting hope. A Scot born in Demerara (present-day Guyana), where his father and uncle made so much money running slave gangs that they bought themselves some sugar plantations, Fraser was later brought up in a Scottish castle his father bought at Skipness in Argyll, before taking his place at Harrow and eventually arriving in Japan in 1862.

Everyone playing that day must have heard how, in that game between a Liverpool team he was playing for and an All-England XI, Fraser had hit a ball from England fastest bowler of the day, John “Foghorn” Jackson, over the boundary for six — and how Jackson was not amused. “The next ball came straight at me about the height of my neck, and if I had not luckily avoided it I don’t think I should have ever seen Japan,” Fraser wrote of the incident later.

But alas, in Yokohama perhaps such good fortune deserted him, because Fraser never publicly revealed anyone’s scores or the result. The game did, however, live on through Harrow’s 1910 “School Register,” where Fraser’s entry reads in part: “Captained the Yokohama side in a cricket match (Yokohama vs the Fleet) played in curious circumstances at Yokohama in 1863.”

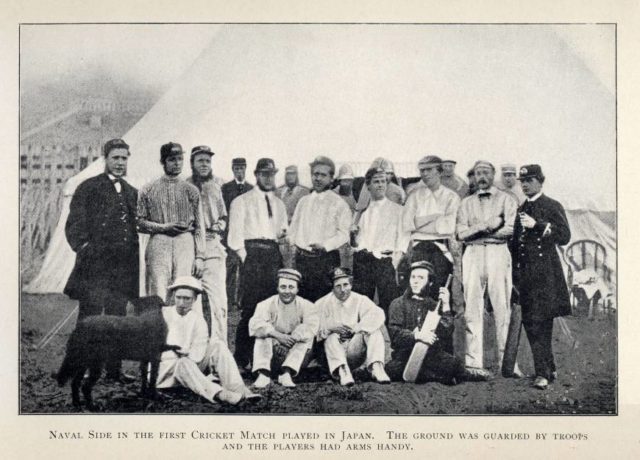

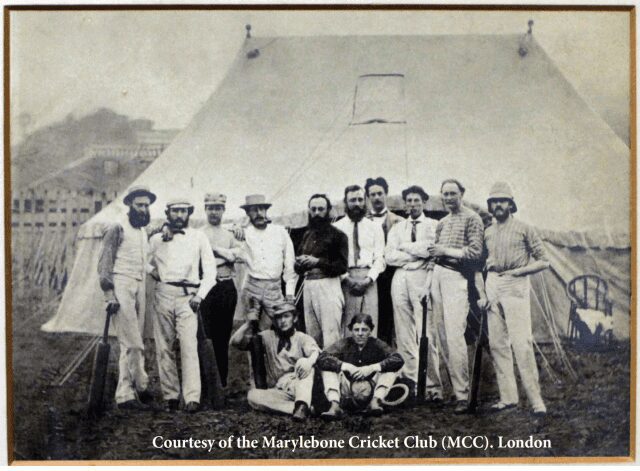

Fraser himself also sent the MCC at Lord’s Cricket Ground in London (then as now, the game’s governing body) an account of the game and photographs of both teams with the players identified. One of these pictures, located in the MCC archives only this January, is by far the oldest photo relating to Western ball games in Japan.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the globe just two months after Fraser’s 1908 article in the magazine Cricket, Adm. Sir Harry Holdsworth Rawson, the governor-general of New South Wales in Australia, gave a speech that cast an amusing new light on the event. “He recalled,” the Sydney Morning Herald newspaper reported, “the first cricket match played in Japan, in 1863 — a remarkable feature of which was the fact that half the players were playing football.”

Fraser, Markham, Rawson and the others would surely turn in their graves if they knew that for nigh on 100 years their game had been lost to history. Instead, a relatively mundane encounter between the Navy and the Garrison in November 1864 was long believed to be Japan’s first cricket match.

The reasons any records of the game were lost are twofold: first, no local newspapers from June 1863 have survived; and second, Fraser left Japan in 1868 leaving another Scottish cricketer, J. P. Mollison, to run his trading business. Soon after, though Mollison founded the Yokohama Cricket Club (forerunner of today’s Yokohama Country & Athletic Club [YC&AC]) he ignored the 1863 game in all his speeches and writings — likely because he wanted to go down in history as the man who introduced cricket to Japan.

In fact, it was only by coming across Rawson’s entry in the obituary section of the Wisden cricket website that, last summer, this writer was able to discover the 1863 game ever took place. There, it said: “He played in the first cricket match which ever took place in Japan, being a member of the Fleet team which defeated Yokohama in 1863.”

The degree of embarrassment felt by Fraser about the match can be judged by Markham’s response on reading the Scot’s account: “You have omitted to mention the fact that the Naval team gave you a ‘jolly good licking!’” he wrote.

Though Fraser may have hoped for a “samurai stopped play” call from the umpire, he later reported that “no attack took place on that day or afterwards, and very soon the native population began to return.”

Seven weeks later, however, many of the visiting players would see action when the Royal Navy bombarded the Satsuma clan’s base in Kagoshima, Kyushu, in a bid to extract blood money for Richardson’s killing in the Namamugi Incident. Fortunately for them, none of their names appears on the plaque listing Kagoshima fatalities, which is still in place in the former British Consulate in Yokohama.

A festival celebrating the 150th anniversary of the 1863 match takes place on June 22 at Yokohama Country & Athletic Club, featuring Japan’s men’s and women’s cricket teams, ones from the British Embassy and YC&AC and a re-enactment. J.C. Fraser’s photo album will also be on display. For details, visit